INTRODUCTION

With the risk of malignant melanoma increasing from 1 in 1500 in 1930 to 1 in 75 in the year 2000, being aware of skin moles has never been more important as these are the source of skin cancer (Whited 1998). Each year in the UK 12,800 people are diagnosed with melanoma; a rare and aggressive form of cancer which originates in the skin but can spread to other organs. Within this population, over 50% are women aged 15-34 with the source appearing to be a skin mole (Cancer Research UK 2012).

A mole (Figure 1 & 2) is a small skin lesion formed by a collection of cells called melanocytes which produce the colour pigment in your skin. Melanocytes are found between the dermis and epidermis of the skin and the pigment produced by these cells helps to protect the body from UV light from the sun. Burns to the skin as a result of UV light can lead to the melanocytes becoming cancerous in malignant melanoma (Cancer Research UK 2012).

Figure 1 & 2: A ‘normal’ mole, also known as Melanocytic naevi are small, brown, flat and round and these are the most common type of mole found on skin.

Melanocytic naevi is the most common type of mole and is usually brown, flat and round. Other types of mole include dermal melanocytic naevi, which are usually raised, pale and sometimes hairy, and also compound melanocytic naevi (Figure 3), which are usually raised above the skin, light brown and sometimes hairy (NHS 2012). Over time, moles can change in appearance and number with some moles fading and others becoming more pronounced. It is also thought that they sometimes respond to hormonal changes, e.g. during pregnancy they become slightly darker,

through teenage years they increase in number, and with older age they may disappear completely (NHS 2012).

Within recent years, the incidence and mortality rates of cutaneous malignant melanoma have increased rapidly worldwide and the primary thought for cause is directly related to sun exposure. Excessive sun exposure, particularly during early years, can be accountable for a person developing melanoma originating from a ‘normal mole’. It is thought that more than 70% of melanomas begin in or near an existing mole or dark spot on the skin (Bastuji-Garin 2002). Other suggested causes for the development of cutaneous malignant melanoma are intense but intermittent exposure to sun, as well as phenotypic susceptibility e.g. fair skin and a tendency to burn easily.

There is a wealth of research on sun exposure and sunscreen use in relation to cutaneous malignant melanoma. Elwood (1998) assessed the association between incidence rates of cutaneous malignant melanoma with occupational, intermittent and total sun exposure. In addition to this, the history of sunburn at different ages was accounted for. Generally, a significant positive correlation was present for intermittent sun exposure, in conjunction with a significantly reduced risk for heavy occupational exposure. Also, excess risk for total exposure was marginally significant. Results in relation to risk of sun burn were significantly increased at all ages in adult life, and similarly increased relative risks for sun burn in childhood and adolescence (Elwood 1998). These findings present the specificity of the positive correlation between intermittent sun exposure and risk of melanoma, in contrast to a reduced risk of melanoma with higher levels of occupational exposure.

Controversial evidence surrounds the relationship between the use of sunscreen and the incidence of developing cutaneous malignant melanoma. One would suggest that sunscreen use would have a protective effect on the skin leading to a reduced likelihood of developing melanoma however several studies suggest a negative effect. The relationship between the use of sunscreen and number of naevi (moles) was analysed, using naevus counts to predict subsequent cutaneous malignant melanoma risk. Autier et al. (1998) reported a study performed by asking parents of 6 or 7 year old children how frequently their child used sunscreen, and connecting it to the naevus count. Results showed a significantly higher naevus count with children who used sunscreen (Autier et al. 1998). Paradoxically, a similar controlled study found the opposite results. Gallagher et al. (2000) demonstrated that naevi numbers were decreased in children who regularly use sunscreen. Despite this, this evidence refers to naevi counts therefore any results attained cannot be directly linked to melanoma.

It is well established that exposure to sun and use of sun screen can affect a mole. However, pigmentation factors of skin, as well as host factors such as hair colour and the number of nevi on lower limbs, in conjunction with sun exposure is also thought to be a large predictor to the risk of developing melanomas from a mole. Veierod et al. (2003) suggested that large asymmetric nevus on lower limbs is a strong predictor of developing melanoma risk. Results revealed that females with 7 or more large (>5mm) asymmetric, nevi on their lower limbs had approximately a 5 times higher risk of developing melanoma in comparison to females with no nevi on their lower limbs. This is thought to be the strongest host factor in predicting the risk of developing melanoma. Furthermore, when comparing hair colour, people with blond hair had a 2 times higher risk of developing melanoma compared to brown and black hair, and people with red hair had approximately a 4 times higher risk of developing melanoma. Associating these results with the facts that people with blond and red hair have fairer skin can also be linked to the idea that with sun exposure, people with fair skin are more prone to burning. Results from this study revealed that hair colour is a statistically significant factor associated with the risk of melanoma (Veierod et al. 2003). Supporting evidence for hair colour in association to risk of melanoma was present in two Danish case-control studies however the association between cutaneous sun sensitivity e.g. tanning and burning, and risk of melanoma was much weaker than for the association with hair colour (Osterlind et al. 1988 & Lock-Andersen et al. 1999). A retrospective study in Australia also observed a weak association between cutaneous sensitivity to the sun and risk of developing melanoma (Holman 1984). Finally, results showed that women who had endured sun burn in their second, third and fourth decade of their life were at an increased risk of developing melanoma from a ‘normal mole’ (Veierod et al. 2003).

In conclusion, there are numerous factors which can affect a skin mole. The main host factor in determining if a mole can develop into a melanoma is the presence of large asymmetrical nevi on the lower limbs, followed by hair colour, with individuals with blond or red hair at an increased risk in comparison to individuals with brown or black hair. Other factors which can affect moles are exposure to the sun, sun screen use and previous tanning or burning to the skin.

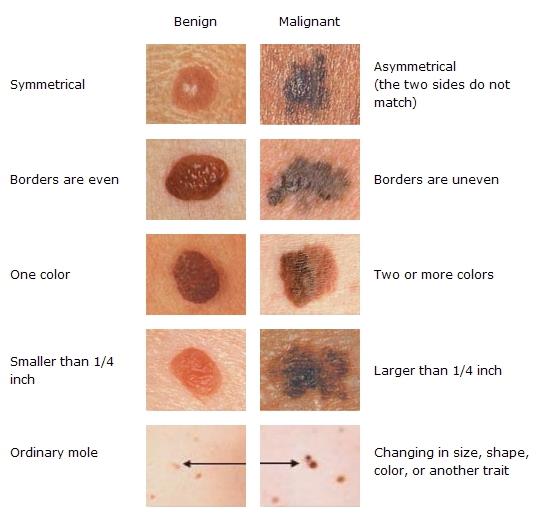

A mole can change in weeks or months therefore skin should be checked regularly for any changes in appearance or numbers of moles, particularly following excessive sun exposure. The acronym ‘A B C D E’ should be used when checking the skin for moles. Figure 4 shows the difference between a normal mole and malignant melanoma.

Asymmetry: a mole which is normal and healthy will usually be round and symmetrical, due to the rate of even growth. A mole which grows at an uneven rate will appear asymmetrical and could be a suspected melanoma.

Border: a normal healthy mole will be have a clearly defined border and will be smooth and round. A mole with a ragged/blurred border, may present as a melanoma.

Colour: a mole suspected of melanoma can consist of different colours e.g. 2 or 3 shades of brown and black and varying shades of pink and red. If a mole becomes darker, this could be indicative of the formation of a cancerous mole. A normal healthy mole will be uniform in colour.

Diameter: a mole which is larger than 6mm or a mole which continually grows can be a suspected melanoma. However, it must be noted that a normal mole can be larger than this or a cancerous mole can be smaller than this 6mm guide.

Elevation/Enlargement: a mole which becomes elevated above the skins surface or appears inflamed/swollen may also present as melanoma. In addition to this, symptoms such as itching, bleeding or crusting are also strong indicators of melanoma.

Figure 4: Taken from Skinipedia.org. The difference between ‘normal’ skin moles on the left versus malignant melanoma on the right according to the ‘A B C D E’ acronym.

Health practitioners, particularly physiotherapists should be aware of the ‘A B C D E’ acronym for assessing moles. Therapists will see a great deal of client skin on a day-to-day basis; therefore they have a unique opportunity to recognise potential skin cancers. Since melanoma is responsible for more than 75% of skin cancer deaths, early detection is an important public health initiative (Neufeld 2013). Early detection is now becoming more dependent on health practitioners (physiotherapists) and non-medical professionals (massage therapists) instead of being reliant on consultants. This is because physiotherapists see and palpate large areas of client’s skin, including the legs and back, which are the areas prone to developing melanoma (Neufeld 2013).

Cancer is a contraindication of many aspects of physiotherapy, however with regards to melanoma, there is conflicting evidence. It was once thought that massage should be a contraindication for patients with cancer due to the concern that increased circulation to the area may cause the cancer to metastasize (move through circulatory or lymphatic system to other places in the body) hence spreading. However, massage, especially oncology massage is specifically adapted for individuals of all ages and types of cancer (Handley 2007). With regards to melanoma, again it was once thought that massage was a contraindication, however more recently research has revealed that patients with melanoma (particularly early stage) only affects the epidermis of the skin with no invasion to the deeper dermis layer. Therefore if massage were to occur over a suspected melanoma, there is no potential for spreading (Cancer Connect 2006). With that said, if a physiotherapist suspects a patient may be at risk of developing melanoma from a mole, the patient should be advised to seek help from their doctor and any massage should be done with caution. In the United States, a study carried out on massage therapists in 2010 revealed that 60% of therapists received skin cancer education as part of their training, with a further 25% receiving further education after training (Campbell 2013). This information re-iterates the fact that therapists play a key role in the early detection of melanoma providing a necessary and valuable service that can potentially save a patient’s life.

Another key part of physiotherapy involves the administration of electrotherapy; namely ultrasound and interferential. Anyone trained in electrotherapy will know that cancer and tumours are a contraindication, however evidence exists which suggests that low level direct current electrotherapy may produce an antitumor effect (Sersa 1993). This idea was tested on malignant melanoma B-16 experimental tumor model in which a significant antitumor effect was witnessed as well as tumor growth delay. It is suggested that low level direct current electrotherapy may be an effective treatment for local treatment of malignant melanoma (Sersa 1993). Supporting evidence for this is present in a study which carried out negative low level direct electric current on a human melanoma skin lesion. After 12 applications, a regression in the tumor mass was observed, suggesting that this electrotherapy can be effective in the treatment of human melanoma skin lesions (Plesnicar 1994). It must be said however that if a patient has suspected melanoma on the skin which is not yet diagnosed as melanoma, the patient should be advised to seek help from the doctor first and any electrotherapy administered must be done so with caution.

To conclude, health practitioners should be aware of how to detect if a patient has a normal mole, or a mole which could develop into melanoma. The acronym ‘A B C D E’ should be used when

assessing if a mole is abnormal and this is an effective, simple method to form an accurate diagnosis. Factors which can cause a normal mole to potentially turn malignant mainly include excessive sun exposure. However this in conjunction with host factors and sun screen use can also be detrimental to a ‘normal mole’. Finally, the physiotherapist should be aware of all the contraindications of the various treatments which they use, particularly when suspecting a patient has melanoma. Despite there being contradictory evidence surrounding massage and electrotherapy, in the case of melanoma, refer the patient to a specialist for accurate diagnosis and suggested treatment. Finally; a ‘normal mole’ is not dangerous, however if exposed to excessive sun in conjunction with host factors, it is possible it will turn into malignant melanoma, a dangerous form of skin cancer.

Referencing

1. Autier, P, JF Dore, MS Cattaruzza et al. 1998. Sunscreen use, wearing clothes, and number of nevi in 6 to 7-year old european children. J Natl Cancer Inst. 90, 1873 – 1880.

2. Bastuji-Garin, S, TL Diepgen. 2002. Cutaneous malignant melanoma, sun exposure, and sunscreen use: epidemiological evidence. British Journal of Dermatology. 146 (61), 24 – 30.

3. Campbell SM, Q Louie-Gao, ML Hession et al. 2013. Skin Cancer education among massage therapists: a survey at the 2010 meeting of the American Massage Therapy Association. J Cabcer Educ. 28 (1), 158 – 164.

4. Cancer Consultants 2012, accessed 3 August 2013, http://patient.cancerconsultants.com/tr … spx?id=821.

5. Cancer Research UK 2012, accessed 24 July 2013, < http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-help/type/melanoma/about/the-skin-and-melanoma>.

6. Elwood, JM, J Jopson. 1998. Melanoma and sun exposure: An overview of published studies. Int. J. Cancer. 73 (2), 198 – 203.

7. Gallagher RP, JK Rivers, TK Lee, CD Bajdik, DI McLean, AJ Coldman. 2000. Broad-spectrum sunscreen use and development of new nevi in white children: a randomized controlled trial. J AMA. 283, 2955 – 2960.

8. Handley WC. 2007. Massage for cancer patients: Indicated or contraindicated? Massage Today. 7 (1), 1-3.

9. Neufeld A, SK Anderson. 2013. Massage Therapists and the Detection of Skin Cancer in Clients. Massage Today. 13 (2), 1-4.

10. NHS Choices 2012, GOV.UK, United Kingdom, accessed 23 July 2013, http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Moles/Pages/Introduction.aspx.

11. Plesnicar A, G Sersa, et al. 1994. Electric treatment of human melanoma skin lesions with low level direct electric current: an assessment of clinical experience following a preliminary study in five patients. Eur J Surg Suppl. 574, 45 – 49.

12. Sersa G, D Miklavcic. 1993. The feasibility of low level direct current electrotherapy for regional cancer treatment. Reg Cancer Treat. 1, 31 – 35.

13. Veierod, MB, E Weiderpass, M Thorn et al. 2003. A prospective study of pigmentation, sun exposure, and risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma in women. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 95 (20), 1530 – 1538.

14. Whited, JD, JM Grichnik. 1998. Does this Patient Have a Mole or Melanoma? The Journal of the American Medical Association. 279 (9), 696 – 701.